Religion Where You Dont Know What to Believe

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the being of God, of the divine or the supernatural is unknown or unknowable.[1] [2] [3] Another definition provided is the view that "human reason is incapable of providing sufficient rational grounds to justify either the belief that God exists or the belief that God does non exist."[two]

The English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley coined the word doubter in 1869, and said "Information technology merely means that a man shall not say he knows or believes that which he has no scientific grounds for professing to know or believe." Earlier thinkers, withal, had written works that promoted doubter points of view, such as Sanjaya Belatthaputta, a 5th-century BCE Indian philosopher who expressed agnosticism about any afterlife;[4] [v] [6] and Protagoras, a fifth-century BCE Greek philosopher who expressed agnosticism nearly the being of "the gods".[vii] [viii] [9]

Defining agnosticism [edit]

Agnosticism is of the essence of scientific discipline, whether ancient or modern. It simply means that a human shall not say he knows or believes that which he has no scientific grounds for professing to know or believe. Consequently, faithlessness puts aside non only the greater part of pop theology, but likewise the greater part of anti-theology. On the whole, the "bosh" of heterodoxy is more offensive to me than that of orthodoxy, because heterodoxy professes to be guided by reason and science, and orthodoxy does not.[10]

—Thomas Henry Huxley

That which Agnostics deny and repudiate, equally immoral, is the contrary doctrine, that there are propositions which men ought to believe, without logically satisfactory evidence; and that reprobation ought to attach to the profession of disbelief in such inadequately supported propositions.[11]

—Thomas Henry Huxley

Agnosticism, in fact, is not a creed, only a method, the essence of which lies in the rigorous awarding of a single principle ... Positively the principle may exist expressed: In matters of the intellect, follow your reason as far every bit information technology will have you lot, without regard to any other consideration. And negatively: In matters of the intellect do non pretend that conclusions are sure which are not demonstrated or demonstrable.[12] [13] [14]

—Thomas Henry Huxley

Being a scientist, above all else, Huxley presented agnosticism as a form of demarcation. A hypothesis with no supporting, objective, testable evidence is non an objective, scientific claim. As such, in that location would be no manner to examination said hypotheses, leaving the results inconclusive. His faithlessness was not compatible with forming a belief as to the truth, or falsehood, of the claim at manus. Karl Popper would likewise describe himself as an agnostic.[15] Co-ordinate to philosopher William L. Rowe, in this strict sense, agnosticism is the view that human being reason is incapable of providing sufficient rational grounds to justify either the belief that God exists or the belief that God does non exist.[2]

George H. Smith, while albeit that the narrow definition of atheist was the common usage definition of that word,[16] and albeit that the wide definition of agnostic was the common usage definition of that word,[17] promoted broadening the definition of atheist and narrowing the definition of agnostic. Smith rejects agnosticism every bit a third alternative to theism and atheism and promotes terms such as agnostic disbelief (the view of those who do not hold a belief in the existence of whatever deity, but claim that the existence of a deity is unknown or inherently unknowable) and agnostic theism (the view of those who believe in the existence of a deity(south), only merits that the being of a deity is unknown or inherently unknowable).[18] [19] [20]

Etymology [edit]

Agnostic (from Aboriginal Greek ἀ- (a-) 'without', and γνῶσις (gnōsis) 'knowledge') was used by Thomas Henry Huxley in a speech at a meeting of the Metaphysical Club in 1869 to describe his philosophy, which rejects all claims of spiritual or mystical knowledge.[21] [22]

Early Christian church leaders used the Greek discussion gnosis (knowledge) to depict "spiritual cognition". Faithlessness is not to be dislocated with religious views opposing the ancient religious movement of Gnosticism in particular; Huxley used the term in a broader, more abstract sense.[23] Huxley identified agnosticism non equally a creed but rather every bit a method of skeptical, evidence-based enquiry.[24]

The term Agnostic is also cognate with the Sanskrit word Ajñasi which translates literally to "not knowable", and relates to the ancient Indian philosophical school of Ajñana, which proposes that it is incommunicable to obtain knowledge of metaphysical nature or ascertain the truth value of philosophical propositions; and fifty-fifty if cognition was possible, it is useless and disadvantageous for final salvation.

In recent years, scientific literature dealing with neuroscience and psychology has used the word to mean "not knowable".[25] In technical and marketing literature, "doubter" can also mean independence from some parameters—for instance, "platform agnostic" (referring to cross-platform software)[26] or "hardware-agnostic".[27]

Qualifying agnosticism [edit]

Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume contended that meaningful statements most the universe are always qualified past some degree of dubiousness. He asserted that the fallibility of human beings means that they cannot obtain absolute certainty except in trivial cases where a statement is truthful by definition (e.g. tautologies such every bit "all bachelors are single" or "all triangles have three corners").[28]

Types [edit]

- Stiff agnosticism (as well called "hard", "closed", "strict", or "permanent agnosticism")

- The view that the question of the existence or nonexistence of a deity or deities, and the nature of ultimate reality is unknowable by reason of our natural inability to verify any experience with annihilation but some other subjective feel. A strong agnostic would say, "I cannot know whether a deity exists or not, and neither can you lot."[29] [30] [31]

- Weak agnosticism (too called "soft", "open", "empirical", or "temporal agnosticism")

- The view that the existence or nonexistence of any deities is currently unknown but is non necessarily unknowable; therefore, one will withhold judgment until evidence, if any, becomes bachelor. A weak agnostic would say, "I don't know whether any deities be or not, only maybe one solar day, if there is show, we can find something out."[29] [thirty] [31]

- Apathetic faithlessness

- The view that no amount of fence can show or disprove the existence of one or more than deities, and if one or more deities exist, they practice non announced to be concerned about the fate of humans. Therefore, their being has piffling to no impact on personal human affairs and should be of little involvement. An apathetic agnostic would say, "I don't know whether whatever deity exists or not, and I don't care if whatsoever deity exists or not."[32] [33] [ failed verification ] [34]

History [edit]

Hindu philosophy [edit]

Throughout the history of Hinduism there has been a strong tradition of philosophic speculation and skepticism.[35] [36]

The Rig Veda takes an agnostic view on the fundamental question of how the universe and the gods were created. Nasadiya Sukta (Creation Hymn) in the 10th chapter of the Rig Veda says:[37] [38] [39]

But, after all, who knows, and who can say

Whence it all came, and how creation happened?

The gods themselves are later than creation,

so who knows truly whence it has arisen?Whence all creation had its origin,

He, whether he fashioned it or whether he did not,

He, who surveys information technology all from highest sky,

He knows – or possibly even he does non know.

Hume, Kant, and Kierkegaard [edit]

Aristotle,[40] Anselm,[41] [42] Aquinas,[43] [44] Descartes,[45] and Gödel presented arguments attempting to rationally prove the existence of God. The skeptical empiricism of David Hume, the antinomies of Immanuel Kant, and the existential philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard convinced many later philosophers to abandon these attempts, regarding information technology incommunicable to construct any unassailable proof for the existence or non-being of God.[46]

In his 1844 volume, Philosophical Fragments, Kierkegaard writes:[47]

Let united states call this unknown something: God. It is naught more than a name nosotros assign to information technology. The idea of demonstrating that this unknown something (God) exists, could scarcely suggest itself to Reason. For if God does non exist it would of class be impossible to evidence it; and if he does exist it would be folly to attempt information technology. For at the very offset, in starting time my proof, I would have presupposed it, non as doubtful merely as certain (a presupposition is never doubtful, for the very reason that it is a presupposition), since otherwise I would not begin, readily understanding that the whole would be incommunicable if he did not be. Merely if when I speak of proving God's existence I hateful that I propose to prove that the Unknown, which exists, is God, then I express myself unfortunately. For in that case I do not prove anything, least of all an existence, simply simply develop the content of a conception.

Hume was Huxley's favourite philosopher, calling him "the Prince of Agnostics".[48] Diderot wrote to his mistress, telling of a visit past Hume to the Baron D'Holbach, and describing how a word for the position that Huxley would later describe equally agnosticism didn't seem to exist, or at least wasn't common knowledge, at the time.

The first time that Grand. Hume found himself at the tabular array of the Businesswoman, he was seated beside him. I don't know for what purpose the English language philosopher took it into his head to remark to the Baron that he did not believe in atheists, that he had never seen whatever. The Baron said to him: "Count how many we are here." We are eighteen. The Businesswoman added: "Information technology isn't likewise bad a showing to be able to indicate out to you fifteen at once: the three others oasis't made upwards their minds."[49]

—Denis Diderot

United Kingdom [edit]

Charles Darwin [edit]

Raised in a religious surroundings, Charles Darwin (1809–1882) studied to be an Anglican chaplain. While eventually doubting parts of his faith, Darwin continued to help in church affairs, even while fugitive church attendance. Darwin stated that information technology would be "absurd to uncertainty that a man might be an agog theist and an evolutionist".[50] [51] Although reticent well-nigh his religious views, in 1879 he wrote that "I have never been an atheist in the sense of denying the existence of a God. – I think that generally ... an agnostic would be the almost correct description of my state of mind."[50] [52]

Thomas Henry Huxley [edit]

Agnostic views are as one-time as philosophical skepticism, but the terms agnostic and faithlessness were created past Huxley (1825–1895) to sum up his thoughts on contemporary developments of metaphysics about the "unconditioned" (William Hamilton) and the "unknowable" (Herbert Spencer). Though Huxley began to use the term "doubter" in 1869, his opinions had taken shape some fourth dimension before that date. In a letter of September 23, 1860, to Charles Kingsley, Huxley discussed his views extensively:[53] [54]

I neither affirm nor deny the immortality of human. I run into no reason for believing it, but, on the other hand, I have no means of disproving it. I have no a priori objections to the doctrine. No man who has to deal daily and hourly with nature can trouble himself about a priori difficulties. Give me such testify as would justify me in believing in annihilation else, and I will believe that. Why should I not? It is not half so wonderful as the conservation of force or the indestructibility of matter ...

It is no apply to talk to me of analogies and probabilities. I know what I mean when I say I believe in the law of the inverse squares, and I will not rest my life and my hopes upon weaker convictions ...

That my personality is the surest thing I know may be truthful. But the attempt to conceive what it is leads me into mere exact subtleties. I accept champed up all that chaff almost the ego and the not-ego, noumena and phenomena, and all the rest of information technology, also often not to know that in attempting even to call up of these questions, the human intellect flounders at in one case out of its depth.

And again, to the same correspondent, May vi, 1863:[55]

I have never had the least sympathy with the a priori reasons against orthodoxy, and I have by nature and disposition the greatest possible antipathy to all the atheistic and infidel schoolhouse. Nevertheless I know that I am, in spite of myself, exactly what the Christian would telephone call, and, so far as I can see, is justified in calling, atheist and heathen. I cannot see ane shadow or tittle of evidence that the slap-up unknown underlying the phenomenon of the universe stands to us in the relation of a Father [who] loves us and cares for us equally Christianity asserts. So with regard to the other great Christian dogmas, immortality of soul and future state of rewards and punishments, what possible objection can I—who am compelled perforce to believe in the immortality of what we call Matter and Force, and in a very unmistakable present state of rewards and punishments for our deeds—have to these doctrines? Requite me a scintilla of bear witness, and I am gear up to leap at them.

Of the origin of the name agnostic to describe this attitude, Huxley gave the post-obit business relationship:[56]

When I reached intellectual maturity and began to inquire myself whether I was an atheist, a theist, or a pantheist; a materialist or an idealist; Christian or a freethinker; I plant that the more I learned and reflected, the less set was the answer; until, at concluding, I came to the conclusion that I had neither fine art nor part with whatever of these denominations, except the concluding. The one affair in which most of these good people were agreed was the ane matter in which I differed from them. They were quite sure they had attained a sure "gnosis"—had, more or less successfully, solved the problem of existence; while I was quite sure I had not, and had a pretty strong conviction that the trouble was insoluble. And, with Hume and Kant on my side, I could non remember myself presumptuous in property fast by that opinion ... So I took thought, and invented what I conceived to be the appropriate title of "doubter". It came into my caput as suggestively antithetic to the "gnostic" of Church building history, who professed to know so much most the very things of which I was ignorant. ... To my swell satisfaction the term took.

In 1889, Huxley wrote:

Therefore, although information technology be, every bit I believe, demonstrable that we accept no real knowledge of the authorship, or of the engagement of limerick of the Gospels, as they have come up down to us, and that nothing amend than more or less likely guesses can be arrived at on that bailiwick.[57]

William Stewart Ross [edit]

William Stewart Ross (1844–1906) wrote under the name of Saladin. He was associated with Victorian Freethinkers and the organization the British Secular Matrimony. He edited the Secular Review from 1882; it was renamed Doubter Journal and Eclectic Review and airtight in 1907. Ross championed faithlessness in opposition to the disbelief of Charles Bradlaugh as an open-ended spiritual exploration.[58]

In Why I am an Agnostic (c. 1889) he claims that agnosticism is "the very contrary of atheism".[59]

Bertrand Russell [edit]

Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) alleged Why I Am Not a Christian in 1927, a classic statement of agnosticism.[lx] [61] He calls upon his readers to "stand on their own ii feet and look fair and foursquare at the world with a fearless attitude and a free intelligence".[61]

In 1939, Russell gave a lecture on The existence and nature of God, in which he characterized himself as an atheist. He said:[62]

The existence and nature of God is a subject of which I tin can discuss only half. If i arrives at a negative determination concerning the first function of the question, the second part of the question does non arise; and my position, equally you may take gathered, is a negative 1 on this affair.

All the same, later in the same lecture, discussing modernistic not-anthropomorphic concepts of God, Russell states:[63]

That sort of God is, I think, not 1 that can actually be disproved, as I think the omnipotent and benevolent creator tin can.

In Russell's 1947 pamphlet, Am I An Atheist or an Agnostic? (subtitled A Plea For Tolerance in the Confront of New Dogmas), he ruminates on the trouble of what to call himself:[64]

As a philosopher, if I were speaking to a purely philosophic audience I should say that I ought to describe myself equally an Doubter, because I practice not call up that at that place is a conclusive statement by which one can prove that there is not a God. On the other hand, if I am to convey the right impression to the ordinary man in the street I think I ought to say that I am an Atheist, because when I say that I cannot bear witness that at that place is not a God, I ought to add every bit that I cannot prove that in that location are not the Homeric gods.

In his 1953 essay, What Is An Agnostic? Russell states:[65]

An agnostic thinks it impossible to know the truth in matters such as God and the future life with which Christianity and other religions are concerned. Or, if not impossible, at least impossible at the present time.

Are Agnostics Atheists?

No. An atheist, like a Christian, holds that we tin know whether or non in that location is a God. The Christian holds that we can know in that location is a God; the atheist, that we tin can know in that location is not. The Agnostic suspends judgment, saying that there are not sufficient grounds either for affirmation or for denial.

Subsequently in the essay, Russell adds:[66]

I think that if I heard a voice from the heaven predicting all that was going to happen to me during the adjacent twenty-4 hours, including events that would have seemed highly improbable, and if all these events then produced to happen, I might perhaps be convinced at least of the existence of some superhuman intelligence.

Leslie Weatherhead [edit]

In 1965, Christian theologian Leslie Weatherhead (1893–1976) published The Christian Doubter, in which he argues:[67]

... many professing agnostics are nearer belief in the true God than are many conventional church-goers who believe in a torso that does not exist whom they miscall God.

Although radical and unpalatable to conventional theologians, Weatherhead'southward agnosticism falls far curt of Huxley's, and short even of weak agnosticism:[67]

Of course, the homo soul will always have the ability to reject God, for choice is essential to its nature, but I cannot believe that anyone will finally exercise this.

United States [edit]

Robert Grand. Ingersoll [edit]

Robert Chiliad. Ingersoll (1833–1899), an Illinois lawyer and politico who evolved into a well-known and sought-afterward orator in 19th-century America, has been referred to as the "Groovy Agnostic".[68]

In an 1896 lecture titled Why I Am An Agnostic, Ingersoll related why he was an agnostic:[69]

Is there a supernatural power—an arbitrary listen—an enthroned God—a supreme will that sways the tides and currents of the world—to which all causes bow? I do not deny. I practice not know—simply I practice not believe. I believe that the natural is supreme—that from the infinite concatenation no link can be lost or broken—that there is no supernatural power that tin answer prayer—no power that worship can persuade or change—no power that cares for man.

I believe that with infinite arms Nature embraces the all—that there is no interference—no chance—that behind every event are the necessary and countless causes, and that beyond every result will be and must be the necessary and countless effects.

Is in that location a God? I do not know. Is man immortal? I do not know. I thing I practice know, and that is, that neither promise, nor fear, belief, nor deprival, can change the fact. It is equally it is, and it volition exist every bit it must be.

In the conclusion of the speech communication he just sums upward the doubter position equally:[69]

We tin be as honest every bit we are ignorant. If we are, when asked what is across the horizon of the known, we must say that we do not know.

In 1885, Ingersoll explained his comparative view of agnosticism and atheism as follows:[lxx]

The Agnostic is an Atheist. The Atheist is an Agnostic. The Doubter says, 'I do not know, but I exercise not believe there is whatsoever God.' The Atheist says the same.

Bernard Iddings Bell [edit]

Canon Bernard Iddings Bell (1886–1958), a pop cultural commentator, Episcopal priest, and author, lauded the necessity of agnosticism in Beyond Agnosticism: A Book for Tired Mechanists, calling information technology the foundation of "all intelligent Christianity."[71] Faithlessness was a temporary mindset in which one rigorously questioned the truths of the age, including the way in which one believed God.[72] His view of Robert Ingersoll and Thomas Paine was that they were not denouncing truthful Christianity but rather "a gross perversion of it."[71] Role of the misunderstanding stemmed from ignorance of the concepts of God and religion.[73] Historically, a god was any real, perceivable force that ruled the lives of humans and inspired admiration, love, fear, and homage; religion was the practice of it. Aboriginal peoples worshiped gods with real counterparts, such as Mammon (money and material things), Nabu (rationality), or Ba'al (tearing conditions); Bell argued that modern peoples were all the same paying homage—with their lives and their children's lives—to these old gods of wealth, physical appetites, and self-deification.[74] Thus, if 1 attempted to be agnostic passively, he or she would incidentally join the worship of the world'south gods.

In Unfashionable Convictions (1931), he criticized the Enlightenment's complete faith in homo sensory perception, augmented by scientific instruments, as a means of accurately grasping Reality. Firstly, it was fairly new, an innovation of the Western Globe, which Aristotle invented and Thomas Aquinas revived among the scientific community. Secondly, the divorce of "pure" science from human being experience, equally manifested in American Industrialization, had completely altered the surroundings, frequently disfiguring it, so as to propose its insufficiency to human needs. Thirdly, because scientists were constantly producing more data—to the point where no single human could grasp information technology all at one time—it followed that human intelligence was incapable of attaining a complete understanding of universe; therefore, to admit the mysteries of the unobserved universe was to be really scientific.

Bell believed that there were 2 other ways that humans could perceive and interact with the world. Artistic experience was how i expressed meaning through speaking, writing, painting, gesturing—any sort of communication which shared insight into a human's inner reality. Mystical experience was how one could "read" people and harmonize with them, existence what nosotros normally phone call love.[75] In summary, man was a scientist, artist, and lover. Without exercising all 3, a person became "lopsided."

Bong considered a humanist to be a person who cannot rightly ignore the other ways of knowing. However, humanism, like agnosticism, was also temporal, and would somewhen lead to either scientific materialism or theism. He lays out the following thesis:

- Truth cannot be discovered by reasoning on the show of scientific data lonely. Mod peoples' dissatisfaction with life is the issue of depending on such incomplete data. Our ability to reason is non a way to discover Truth merely rather a way to organize our knowledge and experiences somewhat sensibly. Without a total, human perception of the globe, one's reason tends to lead them in the wrong direction.

- Beyond what can be measured with scientific tools, there are other types of perception, such every bit ane's power know another human through loving. I's loves cannot be dissected and logged in a scientific journal, merely we know them far better than we know the surface of the sun. They show us an undefinable reality that is even so intimate and personal, and they reveal qualities lovelier and truer than detached facts can provide.

- To be religious, in the Christian sense, is to live for the Whole of Reality (God) rather than for a minor part (gods). Only by treating this Whole of Reality equally a person—good and true and perfect—rather than an impersonal force, tin can we come closer to the Truth. An ultimate Person can be loved, but a cosmic forcefulness cannot. A scientist can only notice peripheral truths, but a lover is able to get at the Truth.

- There are many reasons to believe in God but they are non sufficient for an agnostic to get a theist. Information technology is not enough to believe in an ancient holy volume, even though when it is accurately analyzed without bias, information technology proves to exist more than trustworthy and admirable than what nosotros are taught in school. Neither is it enough to realize how likely it is that a personal God would have to show human beings how to alive, considering they accept and so much trouble on their own. Nor is it enough to believe for the reason that, throughout history, millions of people have arrived at this Wholeness of Reality only through religious feel. The aforementioned reasons may warm one toward religion, merely they fall short of disarming. Notwithstanding, if 1 presupposes that God is in fact a knowable, loving person, as an experiment, and and so lives according that religion, he or she will all of a sudden come face up to face up with experiences previously unknown. One'southward life becomes full, meaningful, and fearless in the face of death. It does not defy reason but exceeds it.

- Because God has been experienced through dear, the orders of prayer, fellowship, and devotion now affair. They create order within ane'south life, continually renewing the "missing piece" that had previously felt lost. They empower i to be empathetic and humble, not minor-minded or arrogant.

- No truth should exist denied outright, simply all should be questioned. Science reveals an ever-growing vision of our universe that should non be discounted due to bias toward older understandings. Reason is to exist trusted and cultivated. To believe in God is not to forego reason or to deny scientific facts, only to step into the unknown and notice the fullness of life.[76]

Demographics [edit]

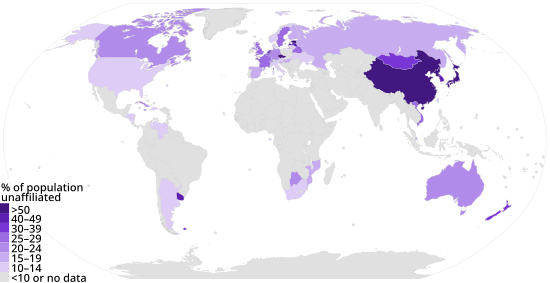

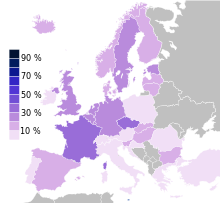

Percentage of people in various European countries who said: "I don't believe there is whatsoever sort of spirit, God or life force." (2005)[78]

Demographic inquiry services normally do not differentiate between various types of non-religious respondents, then agnostics are often classified in the aforementioned category as atheists or other non-religious people.[79]

A 2010 survey published in Encyclopædia Britannica found that the not-religious people or the agnostics made up about 9.6% of the world's population.[80] A November–December 2006 poll published in the Financial Times gives rates for the United states of america and five European countries. The rates of agnosticism in the Us were at xiv%, while the rates of agnosticism in the European countries surveyed were considerably higher: Italy (twenty%), Kingdom of spain (thirty%), Great Great britain (35%), Federal republic of germany (25%), and French republic (32%).[81]

A study conducted by the Pew Research Center found that near 16% of the earth'south people, the third largest grouping subsequently Christianity and Islam, have no religious affiliation.[82] According to a 2012 study by the Pew Research Center, agnostics made up 3.iii% of the US adult population.[83] In the U.S. Religious Landscape Survey, conducted by the Pew Research Centre, 55% of agnostic respondents expressed "a belief in God or a universal spirit",[84] whereas 41% stated that they thought that they felt a tension "being non-religious in a society where most people are religious".[85]

According to the 2011 Australian Bureau of Statistics, 22% of Australians accept "no faith", a category that includes agnostics.[86] Between 64% and 65%[87] of Japanese and up to 81%[88] of Vietnamese are atheists, agnostics, or practise non believe in a god. An official European Marriage survey reported that 3% of the EU population is unsure about their belief in a god or spirit.[89]

Criticism [edit]

Agnosticism is criticized from a multifariousness of standpoints. Some atheists criticize the use of the term agnosticism every bit functionally duplicate from atheism; this results in frequent criticisms of those who adopt the term as avoiding the atheist label.[22]

Theistic [edit]

Theistic critics claim that agnosticism is impossible in practice, since a person tin alive just either every bit if God did not exist (etsi deus non-daretur), or as if God did exist (etsi deus daretur).[90] [91] [92]

Christian [edit]

According to Pope Benedict 16, potent agnosticism in detail contradicts itself in affirming the ability of reason to know scientific truth.[93] [94] He blames the exclusion of reasoning from religion and ethics for unsafe pathologies such as crimes against humanity and ecological disasters.[93] [94] [95] "Agnosticism", said Benedict, "is e'er the fruit of a refusal of that noesis which is in fact offered to man ... The knowledge of God has always existed".[94] He asserted that agnosticism is a choice of comfort, pride, dominion, and utility over truth, and is opposed by the following attitudes: the keenest cocky-criticism, humble listening to the whole of beingness, the persistent patience and self-correction of the scientific method, a readiness to be purified past the truth.[93]

The Cosmic Church building sees merit in examining what it calls "partial agnosticism", specifically those systems that "practise not aim at constructing a complete philosophy of the unknowable, but at excluding special kinds of truth, notably religious, from the domain of knowledge".[96] Withal, the Church is historically opposed to a total denial of the capacity of human reason to know God. The Quango of the Vatican declares, "God, the beginning and cease of all, can, by the natural low-cal of human being reason, be known with certainty from the works of creation".[96]

Blaise Pascal argued that even if there were truly no evidence for God, agnostics should consider what is now known as Pascal's Wager: the space expected value of acknowledging God is ever greater than the finite expected value of not acknowledging his existence, and thus it is a safer "bet" to choose God.[97]

Atheistic [edit]

According to Richard Dawkins, a distinction between agnosticism and disbelief is unwieldy and depends on how close to zero a person is willing to rate the probability of existence for any given god-like entity. About himself, Dawkins continues, "I am agnostic simply to the extent that I am agnostic nigh fairies at the bottom of the garden."[98] Dawkins also identifies two categories of agnostics; "Temporary Agnostics in Practice" (TAPs), and "Permanent Agnostics in Principle" (PAPs). He states that "agnosticism about the existence of God belongs firmly in the temporary or TAP category. Either he exists or he doesn't. It is a scientific question; one day we may know the answer, and meanwhile we tin can say something pretty stiff about the probability" and considers PAP a "deeply inescapable kind of fence-sitting".[99]

Ignosticism [edit]

A related concept is ignosticism, the view that a coherent definition of a deity must be put forward before the question of the being of a deity can be meaningfully discussed. If the chosen definition is non coherent, the ignostic holds the noncognitivist view that the beingness of a deity is meaningless or empirically untestable.[100] A. J. Ayer, Theodore Drange, and other philosophers run into both atheism and agnosticism as incompatible with ignosticism on the grounds that disbelief and faithlessness accept the statement "a deity exists" as a meaningful proffer that tin exist argued for or against.[101] [102]

See also [edit]

References [edit]

- ^ Hepburn, Ronald W. (2005) [1967]. "Agnosticism". In Donald M. Borchert (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Vol. i (second ed.). MacMillan Reference Usa (Gale). p. 92. ISBN0-02-865780-2.

In the most full general use of the term, agnosticism is the view that we do not know whether there is a God or not.

(page 56 in 1967 edition) - ^ a b c Rowe, William 50. (1998). "Faithlessness". In Edward Craig (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Taylor & Francis. ISBN978-0-415-07310-3.

In the popular sense, an doubter is someone who neither believes nor disbelieves in God, whereas an atheist disbelieves in God. In the strict sense, all the same, agnosticism is the view that human reason is incapable of providing sufficient rational grounds to justify either the belief that God exists or the conventionalities that God does non exist. In so far as one holds that our behavior are rational just if they are sufficiently supported by man reason, the person who accepts the philosophical position of agnosticism volition hold that neither the belief that God exists nor the belief that God does not exist is rational.

- ^ "agnostic, faithlessness". OED Online, tertiary ed. Oxford University Press. September 2012.

agnostic. : A. due north[oun]. :# A person who believes that zilch is known or tin can be known of immaterial things, especially of the existence or nature of God. :# In extended use: a person who is not persuaded by or committed to a item point of view; a sceptic. Also: person of indeterminate ideology or conviction; an equivocator. : B. adj[ective]. :# Of or relating to the belief that the existence of anything beyond and behind material phenomena is unknown and (as far every bit tin be judged) unknowable. Likewise: belongings this belief. :# a. In extended apply: not committed to or persuaded by a detail indicate of view; sceptical. Also: politically or ideologically unaligned; non-partisan, equivocal. agnosticism due north. The doctrine or tenets of agnostics with regard to the existence of anything across and behind fabric phenomena or to cognition of a First Cause or God.

- ^ "Samaññaphala Sutta: The Fruits of the Wistful Life". Digha Nikaya. Translated by Bhikkhu, Thanissaro. 1997. Archived from the original on Feb ix, 2014.

If y'all ask me if there exists another world (later on death), ... I don't call back so. I don't think in that style. I don't think otherwise. I don't remember non. I don't think non non.

- ^ Bhaskar (1972).

- ^ Lloyd Ridgeon (March 13, 2003). Major Earth Religions: From Their Origins To The Nowadays. Taylor & Francis. pp. 63–. ISBN978-0-203-42313-4.

- ^ The Cyberspace Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Protagoras (c. 490 – c. 420 BCE). Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

While the pious might wish to look to the gods to provide absolute moral guidance in the relativistic universe of the Sophistic Enlightenment, that certainty besides was bandage into doubt by philosophic and sophistic thinkers, who pointed out the absurdity and immorality of the conventional epic accounts of the gods. Protagoras' prose treatise about the gods began "Concerning the gods, I have no means of knowing whether they exist or not or of what sort they may be. Many things forbid knowledge including the obscurity of the subject and the brevity of human being life."

- ^ Patri, Umesh and Prativa Devi (February 1990). "Progress of Atheism in India: A Historical Perspective". Atheist Middle 1940–1990 Gilt Jubilee. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ Trevor Treharne (2012). How to Evidence God Does Not Exist: The Complete Guide to Validating Atheism. Universal-Publishers. pp. 34 ff. ISBN978-1-61233-118-8.

- ^ Thomas Huxley, "Agnosticism: A Symposium", The Agnostic Almanac. 1884

- ^ Thomas Huxley, "Agnosticism and Christianity", Collected Essays V, 1899

- ^ Thomas Huxley, "Faithlessness", Collected Essays V, 1889

- ^ Huxley, Thomas Henry (Apr 1889). "Faithlessness". The Pop Science Monthly. New York: D. Appleton & Company. 34 (46): 768. Wikisource has the full text of the article hither.

- ^ Richard Dawkins (January 16, 2008). The God Mirage. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 72–. ISBN978-0-547-34866-7.

- ^ Edward Zerin: Karl Popper On God: The Lost Interview. Skeptic 6:ii (1998)

- ^ George H. Smith, Atheism: The Case Against God, pg. 9

- ^ George H. Smith, Atheism: The Case Against God, pg. 12

- ^ Smith, George H (1979). Disbelief: The Case Against God. pp. ten–eleven. ISBN978-0-87975-124-1.

Properly considered, faithlessness is not a 3rd alternative to theism and atheism because it is concerned with a different aspect of religious conventionalities. Theism and atheism refer to the presence or absence of conventionalities in a god; faithlessness refers to the impossibility of noesis with regard to a god or supernatural existence. The term agnostic does not, in itself, point whether or not 1 believes in a god. Agnosticism can be either theistic or atheistic.

- ^ Harrison, Alexander James (1894). The Ascent of Faith: or, the Grounds of Certainty in Science and Faith. London: Hodder and Stroughton. p. 21. OCLC 7234849. OL 21834002M.

Allow Agnostic Theism represent that kind of Faithlessness which admits a Divine being; Doubter Atheism for that kind of Agnosticism which thinks it does non.

- ^ Barker, Dan (2008). Godless: How an Evangelical Preacher Became I of America's Leading Atheists. New York: Ulysses Press. p. 96. ISBN978-i-56975-677-5. OL 24313839M.

People are invariably surprised to hear me say I am both an atheist and an agnostic, as if this somehow weakens my certainty. I normally answer with a question like, "Well, are y'all a Republican or an American?" The two words serve different concepts and are not mutually exclusive. Agnosticism addresses knowledge; atheism addresses conventionalities. The agnostic says, "I don't have a knowledge that God exists." The atheist says, "I don't have a belief that God exists." Y'all can say both things at the same fourth dimension. Some agnostics are atheistic and some are theistic.

- ^ Dixon, Thomas (2008). Science and Religion: A Very Brusque Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN978-0-19-929551-7.

- ^ a b Antony, Flew. "Agnosticism". Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ "ag·nos·tic". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2011. Retrieved November fifteen, 2013.

- ^ Huxley, Henrietta A. (2004). Aphorisms and Reflections (reprint ed.). Kessinger Publishing. pp. 41–42. ISBN978-1-4191-0730-6.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, Additions Series, 1993

- ^ Woodrooffe, Sophie; Levy, Dan (September ix, 2012). "What Does Platform Agnostic Mean?". Sparksheet. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved Nov xv, 2013.

- ^ Yevgeniy Sverdlik (July 31, 2013). "EMC AND NETAPP – A SOFTWARE-DEFINED STORAGE BATTLE: Interoperability no longer matter of choice for big storage vendors". Datacenter Dynamics. Archived from the original on June 20, 2014. Retrieved November fifteen, 2013.

- ^ Hume, David, "An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding" (1748)

- ^ a b Oppy, Graham (September 4, 2006). Arguing almost Gods. Cambridge University Printing. pp. xv–. ISBN978-1-139-45889-four.

- ^ a b Michael H. Barnes (2003). In The Presence of Mystery: An Introduction To The Story Of Homo Religiousness. Twenty-Third Publications. pp. 3–. ISBN978-1-58595-259-5.

- ^ a b Robin Le Poidevin (October 28, 2010). Agnosticism: A Very Curt Introduction. Oxford University Printing. pp. 32–. ISBN978-0-nineteen-161454-five.

- ^ John Tyrrell (1996). "Commentary on the Manufactures of Faith". Archived from the original on August 7, 2007.

To believe in the beingness of a god is an act of religion. To believe in the nonexistence of a god is likewise an human activity of organized religion. There is no verifiable bear witness that there is a Supreme Existence nor is there verifiable evidence at that place is not a Supreme Being. Faith is not cognition. We tin can simply state with assurance that we do non know.

- ^ Austin Cline. "What is Blah Agnosticism?".

- ^ Rauch, Jonathan, Let It Exist: Three Cheers for Apatheism, The Atlantic Monthly, May 2003

- ^ Kenneth, Kramer (1986). World scriptures: an introduction to comparative religions. p. 34. ISBN978-0-8091-2781-8.

- ^ Subodh Varma (May six, 2011). "The gods came subsequently". The Times of India. Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved June ix, 2011.

- ^ Kenneth Kramer (January 1986). World Scriptures: An Introduction to Comparative Religions. Paulist Press. pp. 34–. ISBN978-0-8091-2781-8.

- ^ Christian, David (September one, 2011). Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History. University of California Press. pp. 18–. ISBN978-0-520-95067-2.

- ^ Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval Bharat: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Educational activity India. pp. 206–. ISBN978-81-317-1120-0.

- ^ "Aristotle on the being of God". Logicmuseum.com. Archived from the original on May 30, 2014. Retrieved Feb ix, 2014.

- ^ "Internet History Sourcebooks Projection". Fordham.edu. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved February ix, 2014.

- ^ Williams, Thomas (2013). "Saint Anselm". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Leap 2013 ed.). Archived from the original on Dec 2, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ "Internet History Sourcebooks Project". Fordham.edu. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- ^ Owens, Joseph (1980). Saint Thomas Aquinas on the Existence of God: The Collected Papers of Joseph Owens. SUNY Press. ISBN978-0-87395-401-3.

- ^ "Descartes' Proof for the Existence of God". Oregonstate.edu. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February nine, 2014.

- ^ Rowe, William L. (1998). "Agnosticism". In Edward Craig (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Taylor & Francis. ISBN978-0-415-07310-3. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ Kierkegaard, Søren. Philosophical Fragments. Ch. 3

- ^ A Hundred Years of British Philosophy, By Rudolf Metz, pg. 111

- ^ Ernest Campbell Mossner, The Life of David Hume, 2014, pg.483

- ^ a b Letter 12041 – Darwin, C. R. to Fordyce, John, May 7, 1879. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014.

- ^ Darwin's Complex loss of Religion The Guardian September 17, 2009. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014

- ^ "Darwin Correspondence Project – Belief: historical essay". Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley (1997). The Major Prose of Thomas Henry Huxley . University of Georgia Press. pp. 357–. ISBN978-0-8203-1864-six.

- ^ Leonard Huxley (February 7, 2012). Thomas Henry Huxley A Character Sketch. tredition. pp. 41–. ISBN978-3-8472-0297-4.

- ^ Leonard Huxley; Thomas Henry Huxley (Dec 22, 2011). Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley. Cambridge Academy Press. pp. 347–. ISBN978-1-108-04045-7.

- ^ Huxley, Thomas. Collected Essays, Vol. V: Science and Christian Tradition. Macmillan and Co 1893. pp. 237–239. ISBNane-85506-922-9.

- ^ Huxley, Thomas Henry (1892). "Agnosticism And Christianity". Essays Upon Some Controverted Questions. Macmillan. p. 364.

Agnosticism And Christianity: Therefore, although information technology exist, equally I believe, demonstrable that we have no real knowledge of the authorship, or of the date of composition of the Gospels, every bit they take come downwardly to the states, and that nothing improve than more or less probable guesses can be arrived at on that subject area.

- ^ Alastair Bonnett 'The Agnostic Saladin' History Today, 2013, 63,two, pp. 47–52

- ^ William Stewart Ross; Joseph Taylor (1889). Why I Am an Doubter: Beingness a Manual of Agnosticism. W. Stewart & Company.

- ^ "Why I Am Not A Christian, past Bertrand Russell". Users.drew.edu. March 6, 1927. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- ^ a b Bertrand Russell (1992). Why I Am Non a Christian: And Other Essays on Religion and Related Subjects. Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-07918-1.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand. Collected Papers, Vol 10. p. 255.

- ^ Collected Papers, Vol. 10, p. 258

- ^ Bertrand Russell (1997). Last Philosophical Testament: 1943–68. Psychology Press. pp. 91–. ISBN978-0-415-09409-2.

- ^ Bertrand Russell (March two, 2009). The Bones Writings of Bertrand Russell. Routledge. pp. 557–. ISBN978-1-134-02867-2.

- ^ "'What Is an agnostic?' by Bertrand Russell". Scepsis.net. Archived from the original on August 22, 2013. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ a b Weatherhead, Leslie D. (September 1990). The Christian Doubter. Abingdon Press. ISBN978-0-687-06980-4.

- ^ Brandt, Eric T., and Timothy Larsen (2011). "The Onetime Atheism Revisited: Robert One thousand. Ingersoll and the Bible". Journal of the Historical Society. 11 (ii): 211–238. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5923.2011.00330.x.

- ^ a b "Why I Am Agnostic". Infidels.org. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ Jacoby, Susan (2013). The Great Doubter. Yale University Press. p. 17. ISBN978-0-300-13725-5.

- ^ a b "The Good News, by Bernard Iddings Bong (1921)". anglicanhistory.org . Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ Brauer, Kristen D. (2007). The religious roots of postmodernism in American culture: an assay of the postmodern theory of Bernard Iddings Bell and its continued relevance to gimmicky postmodern theory and literary criticism. Glasgow, Scotland: University of Glasgow. p. 32.

- ^ Bong, Bernard Iddings (1931). Unfashionable Convictions. New York and London: Harper & Brothers. p. twenty.

- ^ Bell, Bernard Iddings (1929). Beyond Faithlessness. New York and London: Harper & Brothers. pp. 12–xix.

- ^ Bell, Bernard Iddings (1931). Unfashionable Convictions. New York and London: Harper & Brothers. pp. 4–five.

- ^ Bell, Bernard Iddings (1931). Unfashionable Convictions. New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishing. pp. 25–28.

- ^ "Religious Limerick by Country, 2010–2050". Pew Inquiry Center's Religion & Public Life Projection. Apr ii, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ "Social values, Science and Technology" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 30, 2011. Retrieved April nine, 2011.

- ^ "Major Religions Ranked by Size". Adherents.com. Archived from the original on Baronial eleven, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Organized religion: Year in Review 2010: Worldwide Adherents of All Religions". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ "Religious Views and Beliefs Vary Greatly past Country, Co-ordinate to the Latest Financial Times/Harris Poll". Financial Times/Harris Interactive. December 20, 2006. Archived from the original on July 23, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ Goodstein, Laurie (Dec xviii, 2012). "Study Finds One in 6 Follows No Religion". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014.

- ^ Cary Funk, Greg Smith. ""Nones" on the Rise: One-in-Five Adults Accept No Religious Amalgamation" (PDF). Pew Research Center. pp. nine, 42. Archived from the original (PDF) on Baronial 26, 2014. Retrieved Nov 21, 2013.

- ^ "Summary of Cardinal Findings" (PDF). Pew Inquiry Middle. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

Nearly all adults (92%) say they believe in God or a universal spirit, including 7-in-ten of the unaffiliated. Indeed, one-in-five people who identify themselves as atheist (21%) and a majority of those who place themselves as agnostic (55%) express a belief in God or a universal spirit.

- ^ "Summary of Key Findings" (PDF). Pew Research Center. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

Interestingly, a substantial number of adults who are not affiliated with a religion as well sense that there is a disharmonize between religion and modernistic society – except for them the disharmonize involves beingness not-religious in a social club where almost people are religious. For example, more than iv-inten atheists and agnostics (44% and 41%, respectively) believe that such a tension exists.

- ^ "Cultural Diversity in Australia". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2012. Archived from the original on May 28, 2014. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ Zuckerman, Phil (2007). Martin, Michael T (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Disbelief. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Printing. p. 56. ISBN978-0-521-60367-vi. OL 22379448M. Retrieved April nine, 2011.

- ^ "Average intelligence predicts atheism rates across 137 nations" (PDF). January 3, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 23, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ Social values, Science and Technology (PDF). Advisers General Research, European Union. 2005. pp. seven–eleven. Archived from the original (PDF) on April thirty, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ Sandro Magister (2007). "Habermas writes to Ratzinger and Ruini responds". Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ "Why can't I alive my life every bit an agnostic?". 2007. Archived from the original on May xvi, 2008. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ Ratzinger, Joseph (2006). Christianity and the Crisis of Cultures. Ignatius Printing. ISBN978-1-58617-142-1.

- ^ a b c Ratzinger, Joseph (2005). The Yes of Jesus Christ: Spiritual Exercises in Faith, Promise, and Love. Cross Roads Publishing.

- ^ a b c Ratzinger, Joseph (2004). Truth and Tolerance: Christian Belief And World Religions. Ignatius Press.

- ^ Benedict XVI (September 12, 2006). "Papal Address at University of Regensburg". zenit.org. Archived from the original on June 1, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ a b Agnosticism. Catholic Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on July i, 2014.

- ^ "Argument from Pascal'due south Wager". 2007. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ The God Mirage (2006), Runted Press, p. 51

- ^ The God Mirage (2006), Bantam Press, pp 47-48

- ^ "The Argument From Non-Cognitivism". Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ Ayer, Language, 115: "At that place tin be no way of proving that the existence of a God ... is even probable. ... For if the beingness of such a god were probable, then the proposition that he existed would exist an empirical hypothesis. And in that case information technology would exist possible to deduce from it, and other empirical hypotheses, certain experimental propositions which were non deducible from those other hypotheses alone. But in fact this is not possible."

- ^ Drange, Atheism

Further reading [edit]

- Agnosticism. Forgotten Books. pp. 164–. ISBN978-1-4400-6878-2.

- Alexander, Nathan G. "An Atheist with a Tall Hat On: The Forgotten History of Agnosticism." The Humanist, February 19, 2019.

- Annan, Noel. Leslie Stephen: The Godless Victorian (U of Chicago Press, 1984)

- Cockshut, A.O.J. The Unbelievers, English Thought, 1840–1890 (1966).

- Dawkins, Richard. "The poverty of agnosticism", in The God Mirage, Black Swan, 2007 (ISBN 978-0-552-77429-i).

- Huxley, Thomas H. (February 4, 2013). Man's Place in Nature. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 1–. ISBN978-0-486-15134-2.

- Hume, David (1779). Dialogues Concerning Natural Organized religion. Penguin Books, Limited. pp. 1–.

- Kant, Immanuel (May 28, 2013). The Critique of Pure Reason. Loki'south Publishing. ISBN978-0-615-82576-2.

- Kierkegaard, Sören (1985). Philosophical Fragments. Organized religion-online.org. ISBN978-0-691-02036-5. Archived from the original on Feb 9, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- Lightman, Bernard. The Origins of Agnosticism (1987).

- Royle, Edward. Radicals, Secularists, and Republicans: Pop Freethought in Britain, 1866–1915 (Manchester UP, 1980).

- Smith, George H. (1979). Atheism – The Case Against God (PDF). ISBN0-87975-124-X. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

External links [edit]

| | Await up agnosticism in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Zalta, Edward North. (ed.). "Atheism and Agnosticism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Agnosticism at PhilPapers

- Agnosticism at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- Albert Einstein on Organized religion Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Why I Am An Agnostic by Robert G. Ingersoll, [1896].

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Faithlessness

- Faithlessness from INTERS – Interdisciplinary Encyclopedia of Religion and Science

- Agnosticism – from ReligiousTolerance.org

- What do Agnostics Believe? – A Jewish perspective

- Fides et Ratio – the human relationship between faith and reason Karol Wojtyla [1998]

- The Natural Faith by Dr Brendan Connolly, 2008

- Nielsen, Kai (1973) [1968]. "Agnosticism". Dictionary of the History of Ideas. Academy of Virginia Library.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agnosticism

0 Response to "Religion Where You Dont Know What to Believe"

Postar um comentário